11

Conflagration And Recrimination

I don’t know what woke me. It was dark: everything was still. The faint scent of dust and eucalypts that was endemic to Australia drifted through the insect screen over my opened window. I got out of bed and wandered over to peer out. Nothing. A small breeze moved in the big gum trees at the far end of the garden. A few stars were visible in the black night. I was about to go back to bed, yawning, when I smelled it.

Smoke.

At first I thought it was a bushfire, and my heart thudded in my chest. I sniffed as hard as I could but the smell didn’t get stronger. Had I imagined it? I went slowly over to the door and opened it.

Jesus! The smoke was coming from downstairs!

There were sensible things one should do in case of fire, such as immediately dialling—

—999, quite. I did know it wasn’t that, here, but what was it? Hell’s teeth!

My thoughts raced. It might be a mere accident, but I didn’t smoke and it wasn’t a very old house, added to which I’d had it all thoroughly inspected before I bought it and there were no problems with old wiring. I hadn’t been cooking anything and certainly not burning anything in the study fireplace.

That left one likely solution, didn’t it?

I headed cautiously downstairs.

If Andrews was down there he could probably hear my heart thumping, I reflected sourly. By the time I reached the half-landing the smoke was choking me and I could see that the front passage was well alight. I could smell petrol, too. The bloody shit!

I rushed back upstairs, hauled my jeans on, grabbed wallet, keys and phone, and made for the back stairs, which led to a short passage and thence the kitchen. The bastard hadn’t got that far, thank God, but it was pretty smoky. Trying not to breathe, I stumbled through the kitchen and escaped, gasping, out onto the back patio. A wide concrete path led to the front sweep. I raced along it.

The front lawn was lit up by the orange-red glare from the front hall, and as I backed off, staring in mesmerised horror, the tall lead-lighted windows on either side of the front door exploded in sheets of flame.

I lost my balance and fell over, but I wasn’t hurt: it was partly the blast of heat but largely shock at the sheer force of the fire.

As I scrambled up I heard a car take off. Hell and damnation!

Then I moved out of range and rang Cassie’s number. It seemed like forever before she answered: my chest actually hurt with the anxiety. Perhaps that was what the expression “heart-rending” actually meant. It was certainly what it felt like: as if my heart was being slowly and excruciatingly torn into pieces in my chest.

“’Lo?” she said groggily at last.

“Cassie! Thank God! Are you okay?”

“What? Is that you, Alex? Yes, of course I’m okay. What’s the matter?”

“The house is on fire. What’s the emergency number?”

“What?”

“Trethewin. The front hall’s gone up in smoke. What number do I ring?”

Numbly she told me. I hung up and rang it. Fortunately the South Australian emergency services seemed to believe me. They warned, however, that it’d take a while for the engine to get there. I just betted it would.

I rang Cassie back. “Where’s the emergency supply of water?”

“Hang on, I’m coming up there. Ring Ben and Mike, they’ll come over.”

“It’s only the house, though,” I said, like a goop.

“RING BEN AND MIKE!” she shouted, hanging up with a crash.

I rang Ben and Mike.

They worked like Trojans to save that bloody house. Andrews hadn’t sabotaged the pump, thank God, but as it worked off the generator it took the sturdy Mike a while to get it going. We connected hoses and more or less managed to keep the fire in check, but we could see it had invaded the drawing-room: that side of the house was going to be a write-off. Um, what was directly above it? A small guest bedroom at the front, then the upstairs passage, and at the back— My bedroom. Ugh. Well, the décor’d be no loss, but— Yeah.

God knows how they did it, but the wonderful South Australian Country Fire Service, staffed, certainly as to the two engines that turned up, entirely by volunteers, was there in just over twenty minutes.

Three hours after I’d first woken up it was all over. The house was saved, though the CFS warned that the bedroom floor wasn’t safe to walk on. The drawing-room and the formal dining-room behind it were burnt out. So was the front hall, but the other side of the house and the kitchen hadn’t suffered much at all.

Gavin was there, boots and all: it had been impossible to stop him. “The Lazy-Boy’ll be okay!”

No-one replied; we didn’t have the strength to.

“Hey, didja have anythink in the safe, Alex?” was next. God!

“Safe?” said one of the firemen sharply.

“In the study—that side,” I sighed. “It’s empty. I’ve barely set foot in the bloody study. I’ve only been in Australia a few weeks.”

“Aw, right. Well, it was arson, no question. I’d say someone’s really got it in for you, mate.”

“Yes, and we know who!” said Cassie viciously.

“Yeah? You better tell the cops, then. Ya had a fire here a bit back, didn’tcha?” he recalled.

“Yes. He burned the stables down,” she said heavily.

“Aw, yeah, I remember. Nutter, is ’e?”

“No, we think he’s just spiteful. The cops nearly caught him in Melbourne, but he ran away during the night. We never dreamed he’d come back here.”

“No,” I agreed sourly. “It’s a long story. I’d say come in and have a coffee while we tell you all about it, but the kitchen’ll still be full of smoke.”

“Yeah. Well, can’t relax, might still be a spark about.”

“Of course,” I said, trying to pull myself together. “You’ve all been marvellous, I can’t thank you enough.”

He looked pleased, but said: “It’s what we do, mate. Can’t risk a bushfire in this sort of country, ya know. English, are ya, mate? –Thought so. Don’t smoke, do ya?”

“No. This fellow who burned the stables down also set fire to a place in Melbourne. It’s just getting so complicated…”

He shook his head. “Sounds like a serial arsonist to me.”

Yes, well, if he wasn’t before, he was certainly going that way. I sat down suddenly on the wet and muddy lawn.

“Alex!” cried Cassie in consternation.

“I’m okay. Just… had it.”

“The horrible man knifed him!” she explained to the fireman and his pal, another fireman.

“Eh?”

“Yeah, he had a great big knife, he slashed him!” put in Gavin. “See, that was up in Byron, he was trying to escape, only Fifi, she’s a great dog, she’s an Alsatian, she’s an Army dog, she stopped him!”

“Eh?”

I laughed weakly. “You may well say ‘eh?’ What a—a farrago of nonsense.”

“Is ’e delirious?” hissed fireman Number Two.

“Nah. Shock. Take ’im down to the other house and make him a cuppa, eh, Cassie?”

“Yes, I will,” she agreed in relief.

“You can lean on me, Alex!” offered the vainglorious Gavin.

“Them two mates’ll help ’im, kid. –OY! YOUSE TWO!”

And with that it was all over bar the shouting and Ben and Mike carted me ignominiously down to Cassie’s house and laid me tenderly on the sofa. What an absolute fool.

The moment Stella Forrest bustled in she completely took over.

“Let me see that leg, Alex.”

“N—”

She whipped the blanket off me—I was still lying on Cassie’s sofa.

“Mum—” said Cassie faintly.

“Didn’t you even check, Cassie? And why’s he here? Why didn’t you put him to bed properly?” Possibly these were rhetorical questions: at any rate she didn’t wait for an answer, she was hauling my jeans off me.

“Ugh!” gasped Cassie in dismay at the sight of the thigh, taking a step backwards.

“Gee,” gulped Gavin in awe. “Is he gonna die of blood-poisoning, Gran?”

“Nonsense, Gavin. Go and boil the jug. –Now,” she ordered in steely tones.

Gavin vanished.

“Um, love, isn’t this a bit on the nose—” began Fred.

“Get me a clean face washer, the cottonwool and the mercurochrome, Fred.”

Fred vanished.

“Mum, it’s been professionally stitched and, um, stuff: would mercurochrome be right?” faltered Cassie.

“Don’t talk nonsense, dear. Go and make us a nice a nice pot of tea.”

Cassie vanished.

“Exactly what have you been doing, Alex?” Stella demanded.

“Escaping a fire?”

“Don’t give me that!”

I gulped. “Uh, well, we did a bit of riding in Victoria,” I admitted.

“What? With that leg?”

Avoiding her steely eye, I muttered: “A great old eventer, it was too good an opportunity to pass up…”

“Men!”

Said it all, really, didn’t it? What incredible depths of scorn the female human voice could attain.

Cassie wasn’t allowed to pour the tea before she’d phoned Dr Michaels and got him to agree to come up here. “Mum, he won’t want—”

“There’s his lungs as well,” she said, as I had a coughing fit. “Get on with it.”

Cassie got on with it.

Gavin had of course resurfaced after plugging the jug in. “What’s wrong with his lungs?”

“Smoke,” said his grandmother briefly.

“Aw. Is that bad for you?”

“It can be,” she replied grimly. “Shouldn’t you be getting ready for school?”

“Aw, heck!”

Cassie had now rung the doctor and hung up. “Um, I thought he could have the whole day off. I mean, he was up half the night.”

“He can go this afternoon, your father will drive him. –Is he coming?”

“Yes. But, um, Alex isn’t an Aussie.”

“What’s that got to do with it? –What were you doing, Fred, making it?” she snarled.

“Um, couldn’t find a clean face washer.”

“Well, make yourself useful: go and pour me a basin of hot water. –From the JUG!” she shouted as he vanished.

Silence fell.

Cassie looked miserably at the mess that was my thigh. “I should have thought… I’m sorry, Alex.”

“So you should be!” said her mother roundly.

She burst into tears and rushed out.

“He isn’t gonna die, is he?” faltered Gavin.

“No! He’s got it infected, that’s all, you silly! Dr Michaels will give him a shot. Have you had a shower today?”

Shuffle, shuffle. “Um…”

“Go and have one. Now!”

Gavin disappeared.

“Right,” she said, as Fred reappeared with a bowl, looking meek. “Gimme that face washer. –Now...”

I draw a veil. At least it wasn’t a full sponge bath.

An annoyed youngish doctor eventually surfaced. By that time we’d downed the tea, Gavin had been informed he couldn’t have lunch because he’d had a huge meal an hour back—when had she found that out?—and Fred had dragged him off to school.

I was informed that I was a bloody fool, I’d got it infected, what the Hell had I been doing to pull the stitches apart like that, and surely I’d been told to report to a hospital after a week, when they’d let me out? Oh, God. The injection hurt, too.

And what pills was I taking? Feebly I explained that I’d finished the course of antibiotics and they’d given me some painkillers but I didn’t really need— Where were they?

“In the house. We’re not allowed in, we had a fire,” I muttered. “But I don’t really n—”

“Ignore him, Doctor. He means the big house, up the hill.”

“I heard the engines last night,” he admitted. “Otherwise I wouldn’t have come.” Hard look at me. “Show me that hand you’ve been hiding.”

Damn. I held out my left hand.

“What?” gasped Stella.

“It’s nothing, just singed—”

Did I want to get it infected as well? “No, don’t put anything on it, Mrs Forrest. You can bathe it in lukewarm water, but that’s all. No pressure.” He wrote a prescription. And another. And—

I shut my eyes.

They ended up agreeing that though I should be in hospital she would take care of me, and if the coughing got worse or there were any signs of fever—

I shut my eyes again.

… Wasn’t it funny, I reflected, how in books the hero comes through the most frightful trials, torture, sadistic villains and all sorts, and emerges pale with suffering but silent as ever in adversity, brave as a lion, not admitting to any slightest twinge of pain, and never, ever gets managed by a helpful middle-aged female for his own good? In fact he never even comes across Stella Forrests, they just don’t exist in his world.

It was only in the real world, I recognised sourly and ungratefully, that injuries hurt like Hell, you felt queasy and scared and not brave at all, and everything went wrong and the ministering angel was not twentyish, curvaceous and willing. And you got blamed for the lot.

… “You know why he came, don’t you?”

I opened my eyes with a start. “What was that, Stella?”

“Dr Michaels. You know why he came,” she stated inaccurately.

“Uh… He heard the fire engines?”

She sniffed. “And the rest! No, he’s been chasing Cassie, that’s why!”

From the doorway good old Fred said uneasily: “Hang on, Stella.”

“He might as well know, Fred. She’s been out with him a couple of times. Took her to some fancy restaurant in Stirling. Well, as fancy as they get, over there, they can all afford to go into the city in their blimmin’ Volvos, of course.”

“She said it was poncy,” Fred reminded her.

“I dare say. The point is she went, Fred. Well, he’s got a nice practice, he’s doing well, and he’s quite a pleasant young man as doctors go. And there’d be no problems about the kiddies’ illnesses, of course!”

“Look, Stella, for Pete’s sake!”

“There’s no sense blinking at facts, Fred, and she isn’t getting any younger.”

Fred was now very flushed. “Rats! She said she was dead bored the whole time: all ’e can talk about is ’imself!”

“I dare say. Nevertheless.”

Fred lost it. “Look, he doesn’t know one end of a horse from another and doesn’t care, she’s not gonna take up permanent with a bloke like that, and if ya wanna know, she told me that last time ’e asked her out she turned ’im down! So will ya just shuddup about ’im! Poor old Alex doesn’t wanna know, and it’s flamin’ female gossip anyway!” He ran down, and panted.

“I’m ignoring that, Fred,” she warned. “Give Mike a ring.”

“What?” he groped.

“Are you deaf? Give Mike a ring! He can give you a hand to get Alex into Cassie’s room!”

Feebly I began: “N—” Too late, Fred was ringing Mike.

… Um, was that good or bad? Um…

Jim Hawkes looked studiously into his mug of tea while Stella gave him the report-cum-harangue. Heaven was halfway merciful, however, because she then bustled out to the kitchen. Scones for afternoon tea.

“Cripes,” he uttered. “How long has—?” Jerk of the head towards the door.

“Several millennia,” I sighed. He gave a startled laugh. “Um, no, since approximately lunchtime the day after the fire, Jim.”

He swallowed. “Goddit. The cops been onto you yet?”

“Thousands of them,” l sighed. “Distinctly unfriendly: I got the strong impression that they suspect me of setting fire to the bloody house in order to claim on the insurance. Absolutely no further sign of Andrews—asking if there was of course antagonised them—and no evidence it was him. Insurance scam or not, it’s definitely all my fault.”

“It would be, mate. How are ya, really?”

I eyed him sourly. “How are you?”

He grimaced. “Infected, second round of antibiotics, N.B.G., third round of antibiotics, green as grass. You?”

“Not much different, but it’s definitely my fault because I rode old Postman over the jumps at the trainer’s place.”

“Eh?”

“Friday of Cup Week. The trainer was a friend of the chap we were staying with. Postman’s a retired eventer with a lot of go still in him.”

“Uh-huh. Does she know?” Another jerk of the head.

“Yes—more or less. The doc grilled me because some of the stitches had given way. I had to admit I’d been a naughty boy.”

He looked at me limply.

“Yeah,” I said sourly.

“By my calculations,” he said slowly, “you may be out of the doghouse same time as me, in other words when me first grandchild turns twenny-one.”

“Have you got—”

“Nah. That’s making it worse, of course. Our Chrissie’s over in Sydney with some bloke that works for a flamin’ wellness centre. According to her mum she’s lost two stone, spends all her spare time on the rock wall—don’t ask, mate—and is so skinny she’s probably not even having her periods any more.”

“Ouch.”

“Yeah.”

After a moment I ventured: “Any other kids, Jim?”

“Yeah,” he admitted with a little smile. “Brian. Only fifteen. Wavering between a future as the Aussie Jamie Oliver—know him? –Yeah; ’nuff said,” he agreed to my expression, “a Formula 1 driver, and somethink weird in computers, don’t ask me what, but it’s got nothing to do with anything in the English language.”

“I see!”

“Yeah, well, I’d like him to come into the business, but ya gotta let them have their heads, don’tcha?”

“Mm. Pity more parents don’t feel that way.”

He gave me a sharp look. “Oh, yeah?”

I swallowed a sigh. “It’s a long time ago… I suppose it was pressure from my grandfather more than anything, really. Pressure on Dad, too, to talk me out of riding for a living. No, well, water under the bridge, and as I was assured fifty million times, it’s not a job that can last past your mid-thirties.”

“Goddit. So the minute some bloke offers you a ride on some ole nag ya leap at it. They know about all this?”

“The family? No, and long may it last. No, well, Australia’s like the moon to them, Jim. More remote, really: they can tell you all about the moon landing but they had no idea where Adelaide is when I bought Trethewin. Possibly if someone blew up the Sydney Opera House it’d get back to them, but nothing much less would.”

“I getcha. Just as well, ya don’t want ya mum panicking.”

“No. Or my sister. Well, in her case panicking and haranguing me: I promised to give it up, etcetera. I didn’t promise, I merely said I didn’t plan to be riding point-to-point any more.”

“That’s precisely the sort of thing they do take as a promise, mate, and hold ya to evermore!”

“So I’ve realised.”

“Right. Um, Perry been in touch?” he asked on a cautious note.

“No—well, I rang him after I got back from Melbourne. He seemed fine, and Fifi’s sailing round the Whitsundays.”

“Yeah, she is. Well, with the odd stop-off here and there: his mate emailed Perry a snap from Port Douglas.” He looked at my blank face. “Well, the nearest centre to the Whitsundays is Bowen, Alex, that’s about eleven hundred K north of Brizzie. Port Douglas is further north, be about another, um, six hundred K, I s’pose. Used to be a complete dump, but these days it’s full of luxury hotels and fancy restaurants. Not that they woulda gone there, bit of a fish barbie on the beach is more their line.”

“So—so she’d be seventeen hundred kilometres north of Brisbane, where she comes from?”

“Yep. No-one’s gonna look for ’er up there, mate!” He laughed.

“No-o… But it is still within the same jurisdiction?”

“Eh?”

I swallowed. “Within Queensland.”

“Yeah, ’course, nothink north of Queensland, ya keep going north, ya fall off the edge! Don’t worry, the average human’s dog facial-recognition skills are zilch, Perry reckons. You ever seen that barmy Inspector Rex thingo?”

“No.”

“Nah, well, it was on SBS, all in German: had subtitles, ya see. Well, it was barmy but he was a nice dog—German shepherd, like her. No, see, the thing is, Perry reckoned it wasn’t just one dog, they had several different ones for the close-ups or the jumps and, uh, other stuff. Swimming, I think. And obeying their barmy commands, not.”

“Er—not?”

“Nah, dogs don’t understand whole flamin’ speeches, mate, not even when ya speaking German to a German shepherd!”

“I see. Oh! I do see, yes, Jim. You mean people didn’t realise that more than one dog had been used?”

“You goddit, mate. Fifi’s safe. Actually, Perry was wondering if ya might like her down here. Guard the place until we’re sure flamin’ Andrews isn’t gonna have another go. Boy, would I like to see her take another piece out of that bugger,” he said longingly.

“Me, too. But, um, well, are the cops still looking for her?”

“Perry doesn’t think so, but thing is, they’ll never look for her this far from home, will they? Well, SA is a different jurisdiction!” he grinned.

“Yes, of course… I’ll think seriously about it, Jim.”

“Yeah, do that. Perry wouldn’t mind coming over, actually: he’s still well in the doghouse with Junie. Not least because little Tanya’s missing Fifi and keeps asking when she’s coming home.”

“Oh, Hell.”

“Yeah, well, such is life!” he said cheerfully. “But Perry’d be a bloody handy bloke to have on the premises, ya know.”

“Yes, but what about his business?”

“He can keep an eye on the orders and the stock count by email and his helpers can run the shop, no worries. One’s a middle-aged dame, doesn’t know all that much about wine but she’s shit-hot on the accounting side, and the other’s a young bloke with a natural palate that’s learning the business, keen as mustard. He might wanna buy a few lemons, but it wouldn’t be a tragedy if ’e did.”

“I see… Look, I’ll phone Perry. I’d certainly feel more comfortable with him here, and if he can get Fifi here safely that’d be great.”

“Yeah, no worries, mate!” he beamed. “Um, what sort of state is your house in?”

I made a face. “I’m not allowed to go up there, Jim. Cassie and the winery guys have reported that the firemen have ensured it’s safe but it still stinks of smoke. The two guys have cleared out the burnt half of the ground floor: they’ve been great. The other half is more or less habitable and the back stairs are okay, but the front hall, the main staircase and the whole of the left-hand interior of the house as you look at it from the front will need rebuilding. The outer walls look pretty sound but will need to have an expert check them out before we start renovations.”

“Right. Look, me brother-in-law’s a builder, he’d be glad to do the job for you. He can give you references. And Clarysse’ll suss out the right types to inspect it for you, no sweat.”

Oh, dear. I felt quite limp. I hadn’t expected things to start moving so soon… And I’d have to do something about contacting the firm and the family: they’d all be wondering when the Hell I was coming back…

Jim heaved himself up. “You look a bit done-in, Alex, mate. I’ll see if those scones are gonna eventuate.” With which he hurried out, kitchenwards.

I just sagged against my pillows, or strictly speaking, Cassie’s pillows. She was now in the lower bunk in Gavin’s room, he was in the top bunk (with the railing up, his grandmother wasn’t going to risk another round of concussion—“It wasn’t even here, Gran!”) and the senior Forrests were crammed into the tiny spare room. It did have two narrow divan beds, but there was only a foot of floorspace between them.

… “Here we are! Scones and strawberry jam!”

I came to with a jump. “Scones and strawberry jam? Lovely, Stella. Thank you so much.”

I didn’t need them. That was meal four of the day: breakfast, morning tea, lunch… Oh, well. We ate deliciously fresh scones and strawberry jam. Poor old Fred, who’d gone off “to check out the veggie garden” up at the house quite some time since, missed out. No, well, we could be thankful for small mercies, because Paula, who’d driven Jim up here, had gone over to the winery with Cassie to sample the delights, not of the wines, but of Miranda’s tea and cakes. The latter homemade and regularly available to visitors to the cellar door. How or if she costed the ingredients I had yet to determine…

My sister took a deep breath. “Stop flimflamming me, Alex!”

I hadn’t been, exactly, but I stopped anyway.

“Why are you staying on there?”

“Sarah,” I said heavily, “I told you: we had a fire. I’ll have to arrange for a builder, and make sure the insurance claim goes through. And I think the police may have more questions, it’s the second time there’s been a fire at Trethewin.”

She sniffed. “A stable lad smoking? Rubbish!”

“They didn’t have any staff by then, it wasn’t a working stables any longer. It was the manager, the crook who’d been embezzling the funds.”

“What?”

“I did tell you before that it was the manager.”

“You said he was an embezzler, yes, but why would he set fire to the place? It’d only get him deeper in the poo!”

“The easiest way of destroying all the records. The blaze started in the office.”

“All right, but that was ages ago, Alex: why should it hold you up now?”

“I’m trying to explain. It was probably the same man who set fire to the house—there’s no doubt it was arson, there were clear traces of petrol, the front hall and the drawing-room had been soaked with it.”

“Rubbish! Why on earth should he bother?”

I didn’t reply.

“Alex! I said why on earth should he bother?”

I sighed. “Because I’d been chasing him all over the country and caught up with him, um, in a seaside town in New South Wales. Then he escaped again.”

“Alex, are you drunk?” she demanded dangerously.

“No. Nor feverish,” I said heavily.

Short silence. Then: “Why would you be feverish? What are you not telling us? –Alex! Answer me!”

“Look, I’ve got an infected cut on my thigh, that’s all.” Unfortunately I then had a coughing fit. “Um, and a bit of a cough from the smoke,” I added glumly.

“What do you mean, a cut on your thigh? Did you fall off a horse, when you promised you wouldn’t ride point-to-point any more?”

“I didn’t pro— I did not fall off a horse!”

She dropped that one, for the nonce, in favour of: “Just how bad are your lungs?”

“They’re n—” Blast! I had to cough again. “It’s just my throat,” I said weakly. “A bit scratchy, that’s all.”

Another deep breath. “I’m coming out there.”

Oh, God. “Don’t do that, you’d send Mum into a tizz. I’m not an invalid, but I’m on antibiotics for the cut and the doc’s told me to stay put until it’s properly healed. And I’m being very well looked after, Trethewin’s former housekeeper is here, she couldn’t be coddling me more if she was Mum herself.” There was an unconvinced silence from the phone, so I added feebly: “She bakes wonderful scones.”

“I still think I should come out there… How long are you planning to stay?”

“Sarah, I don’t know!”

“What about the firm?”

To Hell with the firm! Uh— Temperately I said: “They seem to be managing perfectly well without me.”

“That awful Neil Plowden’s just itching to step into your shoes, if you don’t look out he’ll be staging a coup behind your back!”

“He’s perfectly competent,” I said mildly.

“That isn’t the point! Do you want him to talk the board into getting rid of you? Because I wouldn’t put it past him.”

If only he would. I sighed.

“Well? –Alex!”

“Look, would it matter if there wasn’t a bloody Cartwright at the helm?” I said heavily. “The whole venture was Grandfather’s baby, you know. Dad just went along with it—he never really enjoyed it the way the old man did. He couldn’t wait to get shot of it. The business is solid, it’s making money, we’ve got excellent pilots and a decent fleet. No-one would miss me. And Plowden knows the business backwards and genuinely adores the whole aeronautical thing into the bargain. You just don’t like him because he doesn’t wear an old school tie and butter you up because you’re a Cartwright.”

I could hear her taking a deep breath. Then: “I’m coming out there,” she stated grimly. “You’re not yourself.”

“For Heaven’s sake, Sarah—!”

She rang off.

My sister was now thirty-eight and as determined as she’d been at the age of eight, when she’d “reported” me to Dad for illicitly riding our then neighbour’s seventeen-hands chestnut hunter, Redskin, and even more illicitly jumping a couple of hedges on him and even more illicitly than that, falling off him over the last. Sarah never told tales, but when she felt it her duty to do so, she reported. She might not have said anything—she didn’t like the neighbour in question—but for the falling off. Dad was not an intrepid man by nature and had been duly horrified. After that he began to think seriously about moving—the country place we were in belonged to Grandfather but he was seldom there: he also had a flat in London, much nearer the office. True, it took a couple of years before we did move, Dad was never into snap decisions. And naturally it had to be a house that Mum liked, but as she was inclined to like anything with a few pretty trees near it and a garden full of pretty flowers, there was plenty of choice in gentrified rural England.

“Is that her?” said Cassie as a tall, handsome dark-haired woman in green competently manipulated an airport trolley full of luggage.

“No. Close but no cigar,” I replied morosely, trying to shuffle the bloody crutch, reinstated by Michaels, out of sight behind me.

“You’d better not put too much weight on that leg, Alex,” she said anxiously.

“Nah, ’cos you’ll split your stitches again and Dr Michaels, he’ll wash his hands of you!” Gavin added with relish.

I sighed. Why had Sarah decided to arrive on a Saturday and why had Stella ever agreed that Gavin could come with us to Adelaide airport and, in short, why had I ever been born?

“Is that her?”

Tall, handsome, dark-haired woman in a smartly-cut black suit. “No. Granted she’s got several suits like that, but no,” I sighed.

“Here’s more!” cried Gavin as the trickle of presumably first-class or business-class passengers was suddenly followed by a flood of scruffier, tired-looking ones.

“Mm. Dark hair, competent-looking,” I reminded them.

They peered. I stared glumly in front of me. She’d find us, I was quite, quite sure.

… “Alex! Alex! Over here! Alex!”

Bingo.

“Help!” gulped Cassie—possibly in response to the scowl, visible even at this distance.

“Ugh, yuck,” noted Gavin.

Well, yes. I waved—pointlessly: she’d seen us, and we couldn’t cross the barrier separating the arriving sheep from the waiting go— What? The reason for Gavin’s disgust was now apparent. Small, plump, short mop of black curls, jumping up and down.

“Uncle Alex! Uncle Alex!”

Cassie was beaming all over her face. “Is that her daughter?”

“Mm. Molly. She should be in school,” I noted heavily. Matters such as the legality—or illegality—of giving one’s kids unofficial holidays never had mattered to Sarah. Well, not when it was her kids and she had a definite purpose in mind. Though what purpose she could possibly have in dragging little Molly, aged nine—

“You look terrible,” my sister greeted me.

“Rats. –Hullo, Molly, darling! Welcome to South Australia!” I greeted my excited niece, who had now thrown her arms round me.

“Don’t dare to lift her up, I can see that crutch you’re trying to hide,” my sister announced grimly.

Oh, God. I detached Molly, and kissed her cheek.

“Are you sick, Uncle Alex?”

Oh, God!

“No. I had an infected cut on my le—” I stopped to cough. “And a bit of a cough,” I added feebly. “But the cut’s lots better and I’ve almost stopped coughing.”

“It sounds like it,” noted Sarah grimly. “And who’s this?” –Hard look at Cassie, who duly quailed.

“This is Cassie Forrest, the acting manager of Trethewin Stables. My sister, Sarah Brathwaite, Cassie,” I added redundantly.

“Goodness! Aren’t you a little young to be managing the stables, dear?” was the immediate response from my blasted sibling.

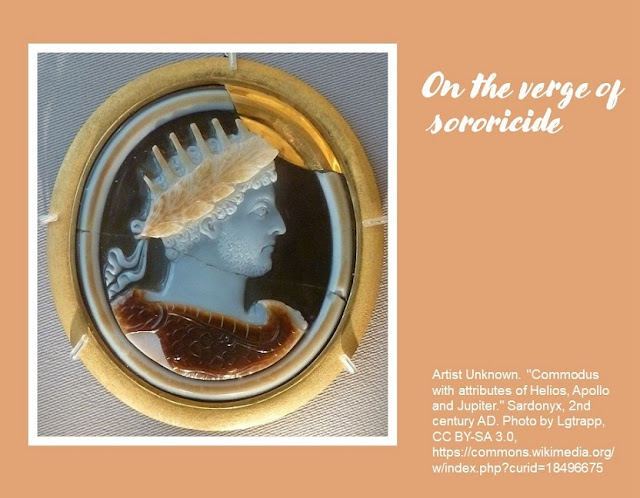

On the verge of sororicide, I replied: “Given that the stables consist of a burnt-out hulk and a handful of retired nags eating their heads off, no, Sarah. And why the Devil have you brought Molly, when she should be in school?”

She awarded me an evil look. “She’s had pneumonia.”

Gavin, who of course had been glaring suspiciously at Molly what time she glared suspiciously back, both with hackles raised, ready to go for the throat, like two cats when one invaded the other’s territory, now brightened. “I had concussion!”

“And you’re now back at school,” I got in swiftly. “This is Gavin, Molly. –He’s only with us because today is Saturday and in short, Sarah, why are you here, with or without Molly, with or without pneumonia, when I told you I was perfectly all right?”

She looked down her nose at me. –Sarah is five-foot-ten to my six foot, but in this case the heels were helping. “Stomping shoes”, we used to call that style in our youth: something that, together with almost everything else, she’d apparently forgotten in the interim. Certainly things like sibling solidarity.

“Because I know you, Alex Cartwright.”

“Right. And is poor Mum now in a tizz, or merely panicking?”

“No! She said I’d better come and make sure you weren’t being silly as usual!” she flashed.

Into the silence that followed this remark little Molly offered: “Granny said you were sure to be much worse than you said, Uncle Alex, and Mummy had better come and look after you.”

Gavin was instantly activated. “Huh! My gran, she’s looking after him, see? She does bandages and ointment and everythink!” He panted slightly. “We say ‘Gran’; ‘Granny’, it’s sissy!”

“’Tis not!”

“’Tis, too!”

“Stop it, Gavin,” said Cassie unconvincingly. “Some people say ‘Granny’, or ‘Nan’, or ‘Nanna’, and Giulia and Tony Guicciardini, they say ‘Nonna’, don’t they? Not everybody has to be the same as us. And Molly’s English: I dare say lots of people in England say ‘Granny’.”

Molly was a just-minded child. “Yes, or ‘Grandma’,” she acknowledged.

“Of course,” Sarah agreed, clearly getting her second wind. “Yours, is he, my dear?”

Reduced to silence by this last gracious appellation, Cassie was pre-empted by her ubiquitous nephew. “Nah! ’Course not! She’s my aunt, see? My mum, she was drowned when I was only three, I can’t remember her. Or my dad: he was drowned, too.”

“Um, my older brother and his wife,” said poor Cassie in a stifled voice.

For once in her life bloody Sarah was thoroughly taken aback. “I’m so sorry,” she said lamely.

Cassie tried to smile. “It was a long time ago: Gavin’s nearly eleven now.”

“I’m nearly ten!” lied Molly vaingloriously.

“Well, nearly nine and a half,” I conceded. “So you had pneumonia, did you, sweetheart?”

“Yes. I had to go to hospital. I had antibiotics; did you have antibiotics, Uncle Alex?”

“Yes, stuffed full of antibiotics. They clear up an infection in no time, don’t they? Come on: take my hand and we’ll find the car.”

“My bag has to come with us,” she said anxiously.

“I’ve got your bag, silly,” sighed Sarah.

I eyed her drily. “No sinecure, traversing the orb with a juvenile in tow, is it?

“Shut up, Alex. And don’t imagine you’re going to fob me off with a hotel, we’re coming home with you.”

Yes. Right. Okay. Holding Molly’s little hot paw tightly for moral support, I headed resignedly for the car in the far reaches of the sprawling carpark…

… “This can’t be right!”

“Yes,” I said firmly.

“Alex, it’s the middle of nowhere! We’ve been driving for hours!”

“Sarah,” I said heavily, “that was not Heathrow, Adelaide is not London, South Australia is not England.”

“I thought it was a nice country house!”

Er… Whatever had given her that idea?

“Nah, it’s half burnt up, see,” contributed the helpful Gavin from the back seat where he was grumblingly immured next to Molly. Possibly a mistake, but there hadn’t been much choice, given that I wasn’t supposed to drive with the damned leg and Sarah had insisted the leg should go in the front and then taken a window seat, ordering Molly to sit beside her.

“Just hush, Gavin,” sighed his aunt from the driver’s seat.

“Well, where are we?” demanded Sarah discontentedly as acres of South Australian hills fled by us.

“Halfway between halfway to Outer Woop-Woop and Adelaide,” I replied.

“Just stop it, Alex! I’m not in the mood for your nonsense!”

“On the contrary, it’s a perfectly valid dialectal expression. ‘Outer Woop-Woop’ is approximately equal to ‘the back of beyond’. Trethewin is only about halfway to the back of beyond, it’s got running water and electricity.” I waited, but the Almighty was merciful and Gavin didn’t say “Unless there’s a bushfire.”

“Running— What are you talking about?” she gasped.

“Er… The tyranny of distance, I think it’s called, Sarah.”

She breathed heavily.

“Um, it’s only about two and a half hours from the city, but we had to get through the Saturday traffic. The airport’s on the wrong side of the city for us,” ventured Cassie.

“I see,” she replied grimly.

Silence fell but unfortunately Molly broke it with: “Where are all the houses?”

“This is the country, Molly,” stated her mother grimly.

“But there aren’t any fields,” she replied in bewilderment.

“No. This is Australia,” said Sarah through her teeth.

“But where are the kangaroos and koala bears?”

Good question. Oops—not. Her mother was grimly informing her: “Molly, you are not getting a koala bear. I’ve told you before, koala bears are wild animals, people don’t keep them as pets.”

“Um, we don’t get many kangaroos round our way,” Cassie contributed feebly.

“We got koalas,” noted Gavin fairly. “Well, some, only ya don’t see them during the daytime, they’re always asleep. Ya can hear them at night in the mating season, they kinda grunt, eh, Cassie?” Helpfully he produced a revolting noise that was halfway between a grunt and a hoarse bark.

“Um, yes, it’s the males, I think,” said Cassie in a small voice into the silence emanating from the stunned Pommies in the car.

“Oh, of course!” I realised with a laugh. “Like rutting stags!”

After a moment Sarah asked on a weak note: “Is this a joke?”

“Nah, ’course not!” Gavin retorted smartly.

“Um, no, Mrs Brathwaite,” Cassie agreed, sounding squashed.

Well, damn bloody Sarah! The “wogs begin at Calais” mentality and then some! “No, and one doesn’t say ‘koala bears,’ while we’re on the subject of the local fauna, Sarah. They’re not bears. No relation at all. They’re marsupials. –With pouches,” I elaborated.

“Yeah, they keep their babies in their pouches,” Gavin agreed indifferently.

“I wish I could see one,” said Molly wistfully.

Silently I determined, under cover of Gavin’s involved explanation in re going down the back up at the big house, where the big gum trees were, and ya might see one, only ya hadda really peer, only they weren’t always, etcetera—I determined that I would buy Molly the loveliest, cuddliest, most realistic toy koala with a baby in its pouch in the whole of Australia. Um, these days it’d probably be made in China, true. Nevertheless.

“Is there a special word for the young ones?” I asked. “I know one says ‘joeys’ for baby kangaroos.”

“Or wallabies,” agreed Gavin.

“Er—mm. But baby koalas?”

“Dunno. Just baby koalas, I s’pose,” the gallant boy replied, as his aunt was silent.

“That’s the only expression I’ve ever heard, but I’m just an ignorant Pommy,” I admitted.

Short silence.

“Ask David Attenborough!” Cassie squeaked. Forthwith she exploded in helpless giggles, so much so that the car wove all over the long, completely deserted, dusty country road and she had to pull into the side.

I laughed, too—more relief than anything.

“Why not? He’d know!” urged Gavin. “He knows all about animals! Hey, didja see the one about the Aussie lizards? That was great! See, he had this great big perentie, it—”

When that was over his aunt said feebly: “Gavin, I was joking. David Attenborough’s English.”

“But heck, you could ask him! He’d know! You could write him a letter!”

“Does he know about koalas?” asked Molly.

“Yeah, ’course! Write and ask him, Cassie!”

“Gavin, he’s famous, he’s a sir and everything, and he’s an old man, we can’t possibly pester him with something like that.”

“But it’s about animals!” he protested.

“No.”

“All right, I’ll write him a letter!” he declared grimly.

“Ooh, so will I!” cried Molly. “We could put them in the same envelope! That’d save a stamp, wouldn’t it, Mummy?”

Sarah was actually heard to swallow, hah, hah!

“Your parsimony is catching up with you,” I noted pleasedly.

“Stop it, Alex. –I don’t see why the children shouldn’t write to him,” she stated pugnaciously.

So be it. Gavin and Molly, aged ten and nine respectively, would write to Sir David Attenborough from Trethewin, South Australia, to ask him what in blazes was the name for the young of the koala. One could only hope and pray that the BBC gave him fleets of secretaries and secretaries’ helpers to open the immense floods of mail he must get from like-minded youngsters and assorted adult cretins who didn’t know better from all over the world…

Was there any hope that the pair of them would forget all about it? Er…

… “This can’t be it!” my sister gasped.

“No, it isn’t,” I agreed heavily. “This is Cassie’s house. Would you mind awfully driving up to the big house, please, Cassie? –Thanks. –It’s uninhabitable, even the untouched side still stinks of smoke, Sarah, but I realise you won’t be satisfied until you’ve seen it with your own eyes.”

Her retort was, as we bumped up the uneven track: “Next you’ll be claiming this is the front drive!”

“Nah, it’s the back way, see,” explained the innocent Gavin—give that boy a medal! Two medals!

… “Silent upon a peak in Darien,” I murmured in Cassie’s ear as we all stood on the lawn while my gobsmacked sibling gaped at the soot-streaked front façade of Trethewin.

“Ssh!”

“This is terrible!” Sarah declared.

“Actually it’s not as bad as it looks,” I admitted. “A building inspector came up yesterday and gave the outer structure the all-clear: that stonework’s extremely solid. It can all be steam-cleaned. What’s left of the interior of that side will have to be ripped out and rebuilt: I’ve had a very reasonable quote for that from a reliable builder. The other side of the house wasn’t touched, but I think all the upholstered furniture will have to be junked; even if we can dry it out there’s not much hope of getting the smell of smoke out of it.”

“Not the big Lazy-Boy!” cried Gavin.

“Which one?” I sighed.

“The one in the study, of course!”

“Oh. Well, it was furthest away, it might be okay, I suppose. We could try airing it. Um, and re-covering it. I suppose if necessary all the padding could be replaced, too,” I admitted without enthusiasm. It wasn’t that the things weren’t comfortable: they were, very. But they were huge, taking up inordinate amounts of room, and the opposite of elegant.

“Yeah, we could do that, eh, Alex?” he agreed eagerly.

“Mm.”

“The wooden furniture should be all right, surely?” ventured Cassie. “The big desk and so on.”

“I think so. Well, if aired.”

“Yes. It seems an awful pity just to junk the sofa and chairs from the family-room, though.”

I swallowed a sigh. “We can try to rescue them, I suppose. But the mattresses and so forth upstairs were completely soaked by the firemen’s hoses, they’ll have to go.”

“I’d forgotten that. We’ll have to hire a couple of big skips, I s’pose.”

“Ooh, yeah!” Gavin agreed eagerly.

“What about the kitchen?” asked Sarah.

“It’s at the back. Just got a bit of smoke. Well, those floral seat cushions can go,” I stated firmly.

“We could try washing the curtains, Alex,” said Cassie helpfully.

I looked at her sweet, eager, anxious face. Okay, I was never going to be rid of those cheery bright blue tartan curtains, was I? “Good idea.”

“And I tell you what: we’ll get all the wooden stuff outside and give it a good wash and let it dry in the sun!” she said eagerly.

“An excellent idea!” Sarah approved. “Can you show me?”

“Yes, of course, Mrs Brathwaite. It’s this way.” They headed off down the side path, Sarah urging her graciously to please call her Sarah.

Oh, boy. That had torn it.

“Uncle Alex!”

I jumped. “Yes, Molly?”

“Where are the trees with the koalas in them?”

“Oh—uh—over there, see? Those tall ones. At the far end of the garden. But If there are any koalas there today they’ll be asleep very high up, you won’t be able to see them.”

“We could look,” she suggested.

If she’d been a simpering brat I wouldn’t have given in. But Molly never simpered. She looked up at me earnestly with big dark brown eyes.

I gave in. “Okay. Take my hand. –Gavin, can you lead the way? Er—not too fast, old chum,” I added feebly, trying to balance the bloody crutch under my free elbow.

“You can lean on me, Uncle Alex!”

“Mm, well, holding your hand will help me to keep my balance, I think, Molly,” I lied.

And with that we set off very slowly and carefully for the far end of the large garden that had once been a showplace but was now showing definite signs of having missed Fred’s loving attentions for some months—though he’d made inroads on the vegetable garden since they came back up here.

There were no koalas in sight, though all concerned agreed that there might be some right up in the tops of the trees where we couldn’t see them. And we returned, limping in the case of one, to the front sweep and my sister’s complete and utter condemnation of the whole venture.

The subsequent discovery of the fact that Cassie had been giving up her bed to me and the further discovery of the further fact that the senior Forrests had given up their room for her (and now Molly as well) and moved down to the winery, were merely minor irritants. Midges after Noah’s flood, kind of thing.

Okay, I would keep off the leg, Sarah, but there was no need for her to look at—

“My God! No wonder you’re limping!”

“It just looks revolting because of the stitches and the remains of Stella’s mercurochro—”

“Shut up, Alex!”

I shut up.

Next chapter:

https://deadringers-trethewin.blogspot.com/2025/07/all-go-at-trethewin.html

No comments:

Post a Comment